BYGONE DAYS: ‘We trust it will prove no more’, hope potato blight will pass by

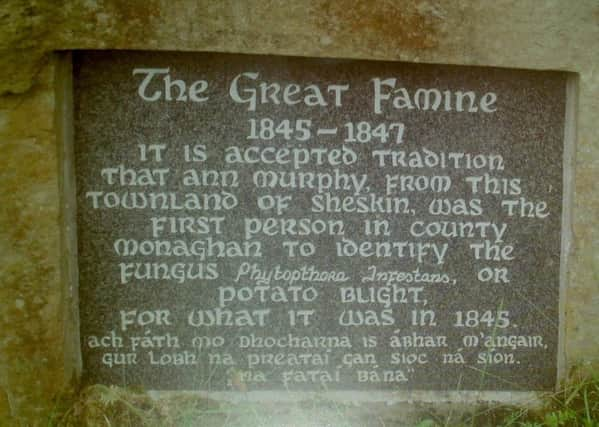

It is reputed that Phytophthora infestans or potato blight made its first appearance in Ireland in the townland of Sheskin, Co Monaghan in August 1845, about three miles outside of the village of Scotstown, which notoriety is now marked by the Famine Stone located at the bottom of Black Hill in the locality.

The News Letter (and other newspapers from the era) capture the growing fear that was spreading across these islands with the dawning enormity of what the potato pestilence and the failure of the crop would mean to the populace of Ireland who were heavily dependant on the potato.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdReflecting on the crisis across Europe the News Letter in September 1845, noted: “We do not know that our statistics are sufficient to ground any general opinion upon the painful and important subject on the partial failure – we trust it will prove no more – of the potato crop. We only know this, that the pestilence has extended through almost every degree of latitude where the esculent has been cultivated, and that neither climate nor soil has saved the plant.

“We find the murrain – if it may be so designated – in the virgin lands of Canada, and in the old cultivated grounds of Normandy. Nor does the disease seem to be confined to any particular species; for though we hear the ‘lumpers’, and the ‘pink-eye’ are more affected in parts of Ireland than other species, we do not read in the American or the Belgian journals that any kinds have been spared by the calamity.

“Again, while in Ireland the blight has not extended beyond the maritime counties, and only very partially, and these, generally, on the eastern coast – we find by the Moniteur that the blight has attacked the fields around Paris – which is a hundred miles inland.

“There are no complaints whatever from the market gardeners in the vicinity of London – a city that lies, as one may say, within hail of the sea.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“From Galway we have no complaints, while from the great Continent westward we learn, that more than half the crop is already lost. South and West of Dublin the plant looks healthy and promises well; on the East and North Coast, a failure is rather considerable.

“In Belgium, it is general; but, we have yet no statistics from the Left Bank of the Rhine, or from Holland. From Austria, the South of Germany, and Italy, we have as yet no accounts; a good omen, we think – for as the harvest is earlier in these parts, the probability is, that we should ere this have heard of a failure, if these countries were visited to any considerable extent with the distemper.”

Of the conditions in Co Fermanagh during this week in September 1845 the Enniskillen Chronicle reported: “There has been no season for many years past that promises so highly for the farmer, as the present. Every crop is crowned with abundance, save only the potato, which we are sorry to say, has been much injured by rot; but from everything we can read, by no measure so injurious as appearances in other parts, both at home and abroad indicate. But for want of space this week we would have given many opinions as to, the failure of this crop.”

The Chronicle published a letter read which had been read by Lord Erne at the meeting of the Erne Estate Farming Society which was held at Lisnaskea.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt had been sent to Lord Erne from a correspondent at Ardrossan, Scotland, on September 6, 1845. It read: “Dear Lord Erne, with regard to the potato failure, I am convinced that there is something radically wrong in the system of cultivation throughout the country, which has impaired the constitution of the potato, and rendered it delicate and liable to failure, particularly in stiff, undrained clay, and imperfect wrought soils, some varieties being more liable to fail than others.

“The advice given by the various writers upon the subject is good so far as it goes, such as planting whole sets, early planting, selecting seeds from high grounds and mountain land, dormant dissection or cutting the sets before tile sap rises, &c.

“But few or any of them discuss the preparation of the land, or the manure, which I conceive to be the most important of all.

“During my experience I have generally found failures are most common on wet stiff land, which, in an unfavourable season, cannot be touched at all, and in a dry season becomes a heap of clods, both of which states are very unfavourable to the potato crop.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The absolute necessity of thorough draining is, therefore, apparent as the first step to be attained.

“I last year made an experiment which was so successful that I feel anxious it should be repeated by others in different parts of the country.

“It was simply this: I spread the manure in autumn, upon a wheat stubble; I ploughed it in with a deep furrow; in this state it remained during the winter; early in spring the sand was well pulverised with grubber and harrows, and drilled up for potatoes, which were planted in cut sets about the 12th of April, without any more manure.

“The potatoes had been out six weeks previous to their being planted, and they consisted of the most delicate kinds, most liable to failure.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The result was perfectly successful; there was not a diseased plant in the field. This might not have been thought so remarkable had I not planted some of the same potatoes, in another field, upon the old system of spreading the manure in drills, putting the potato sets upon it and coveting them up.

“These turned out so complete a failure that I had to sow turnips in place of them, as not one in twenty came up: in every other respect the treatment was the same.”

The letter writer continued: “In attempting to account for these opposite results, I would observe that the potato is, of all vegetables, the most liable to fermentation in the approach of spring, or when placed in contact with any fermenting substance; it should, therefore, be placed, as soon as the frost appears to be gone, in spring, and if the ground is prepared in the autumn previous, the manure being well incorporated with it, there will be no danger of the potato fermenting too rapidly, as it is liable to do when placed upon the dung.

“I believe that by judicious treatment, and, above all, by not manuring the soil too highly, when we want to grow potatoes for seed, the plant may be brought back to its former vigorous condition, and rendered more hardy; for by growing it with too much concentrated manure it has been forced to an unnatural state. A moderately rich, well-pulverizing soil is more essential to the health of the potato than to plant it upon a dunghill.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“To effect the autumn manuring of his potato land, no one deserving the appellation of a good farmer can be at any loss to raise a sufficiency of dung by the month of October, if he cuts and carries his clover, tares, and other green food to be consumed by his cattle in tile house, and having these completed, the most laborious part of the work in autumn; he is enabled to plant the crop earlier in spring, and to gain more time for preparing his land for turnips; again his crop will be fit for digging by the beginning of September, when it can be taken up and stored in dry condition and without any risk of frost.”

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.