BYGONE DAYS: ‘We trust it will prove no more’, hope potato blight will pass by

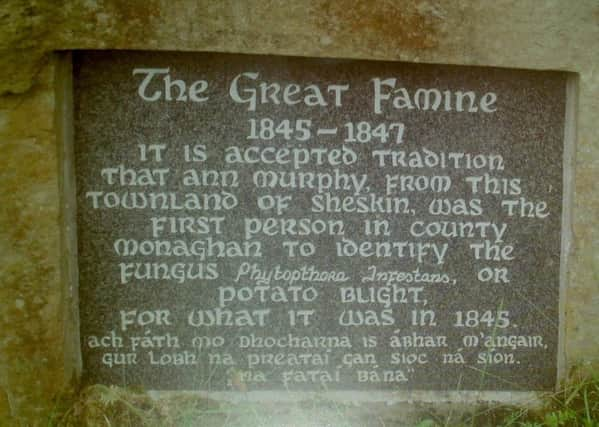

It is reputed that Phytophthora infestans or potato blight made its first appearance in Ireland in the townland of Sheskin, Co Monaghan in August 1845, about three miles outside of the village of Scotstown, which notoriety is now marked by the Famine Stone located at the bottom of Black Hill in the locality.

The News Letter (and other newspapers from the era) capture the growing fear that was spreading across these islands with the dawning enormity of what the potato pestilence and the failure of the crop would mean to the populace of Ireland who were heavily dependant on the potato.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdReflecting on the crisis across Europe the News Letter in September 1845, noted: “We do not know that our statistics are sufficient to ground any general opinion upon the painful and important subject on the partial failure – we trust it will prove no more – of the potato crop. We only know this, that the pestilence has extended through almost every degree of latitude where the esculent has been cultivated, and that neither climate nor soil has saved the plant.

“We find the murrain – if it may be so designated – in the virgin lands of Canada, and in the old cultivated grounds of Normandy. Nor does the disease seem to be confined to any particular species; for though we hear the ‘lumpers’, and the ‘pink-eye’ are more affected in parts of Ireland than other species, we do not read in the American or the Belgian journals that any kinds have been spared by the calamity.

“Again, while in Ireland the blight has not extended beyond the maritime counties, and only very partially, and these, generally, on the eastern coast – we find by the Moniteur that the blight has attacked the fields around Paris – which is a hundred miles inland.

“There are no complaints whatever from the market gardeners in the vicinity of London – a city that lies, as one may say, within hail of the sea.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“From Galway we have no complaints, while from the great Continent westward we learn, that more than half the crop is already lost. South and West of Dublin the plant looks healthy and promises well; on the East and North Coast, a failure is rather considerable.

“In Belgium, it is general; but, we have yet no statistics from the Left Bank of the Rhine, or from Holland. From Austria, the South of Germany, and Italy, we have as yet no accounts; a good omen, we think – for as the harvest is earlier in these parts, the probability is, that we should ere this have heard of a failure, if these countries were visited to any considerable extent with the distemper.”

Of the conditions in Co Fermanagh during this week in September 1845 the Enniskillen Chronicle reported: “There has been no season for many years past that promises so highly for the farmer, as the present. Every crop is crowned with abundance, save only the potato, which we are sorry to say, has been much injured by rot; but from everything we can read, by no measure so injurious as appearances in other parts, both at home and abroad indicate. But for want of space this week we would have given many opinions as to, the failure of this crop.”

The Chronicle published a letter read which had been read by Lord Erne at the meeting of the Erne Estate Farming Society which was held at Lisnaskea.

Advertisement

Hide Ad